Amicus Brief Accepted By Court

Download Amicus Documents here:

Amicus Brief for Aref and Hossain

Memorandum of Law for Aref and Hossain proposed Amicus Brief

Affidavits for Aref and Hossain proposed Amicus Brief (Large download)

Download Press Release

Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Monday, April 19, 2010

CONTACT:

legal issues and information: Colin Donnaruma, (518) 461-5702

info on amicus sponsors: Jeanne Finley, (518) 438-8728

Amicus Brief Accepted By Court In Support Of Albany “Sting” Defendants,

Who Were Preemptively Prosecuted

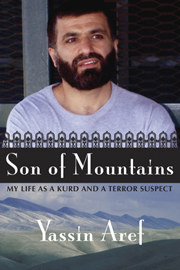

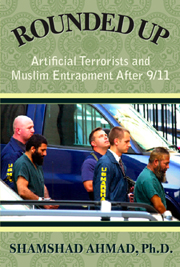

Albany, NY –– On March 30, the United States District Court for the Northern District of New York accepted the filing of an amicus brief (friend of the Court brief) from the Muslim Solidarity Committee (MSC), Project SALAM, and the Masjid As-Salam mosque, all based in Albany, in support of the 2255 applications of Yassin Aref and Mohammed Hossain that were filed on March 10. The amicus brief supports the main assertion of the men’s 2255 applications, which is that they were preemptively prosecuted.

The amicus brief asks that a special prosecutor be appointed to review their convictions to determine whether they were given a fair trial, and whether all exculpatory evidence that was legally required at their trial was produced by the prosecution. Read the amicus brief at amicus_aref_hossain/Aref_Hossain_Amicus_Brief.pdf. Also available at this site are the affidavits in support of the brief from the MSC, Project SALAM, and the Masjid As-Salam.

|

|

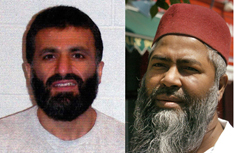

Yassin Aref |

Mohammed Hossain |

Preemptive prosecution is based on the concept that it is better for innocent people to be convicted and incarcerated than to allow even one potential terrorist to remain free. According to the amicus brief, although this concept is illegal, unjust, and reverses the assumption of innocence that is an ancient tenet of criminal law, it has been used to falsely target and frame many innocent Muslims throughout the country in the hysteria following 9/11. An unacknowledged government program of actively targeting and prosecuting Muslims who the government suspects are potential terrorists before they can commit a crime, preemptive prosecution in the case of Aref and Hossain meant that the government created a fictional “sting” operation in order to lure them into supposed terrorism crimes that they had no knowledge of and no intention to commit.

Yassin Aref was the imam at the Masjid As-Salam Mosque on Central Avenue in Albany, and Mohammed Hossain was one of the mosque’s founding members. Both were arrested on August 4, 2004, and on October 12, 2006 they were convicted of terrorism-related charges resulting from the FBI-created sting. They are presently serving prison sentences of fifteen years each.

Although Aref and Hossain’s legal appeals to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals and to the U.S. Supreme Court were unsuccessful (the Supreme Court refused to hear the appeal), an application under 28 U.S.C. § 2255 can be filed by prisoners in the district court where a trial was held, since the application allows evidence to be presented that was not included in the trial and therefore could not be referenced in the previous appeals. Neither man is now represented by an attorney, so their applications were submitted pro se (“for oneself”) and written by them.

Colin Donnaruma, a local civil rights attorney, submitted the amicus brief for the MSC, Project SALAM, and the Masjid As-Salam on behalf of the defendants. “The preemptive targeting of the defendants in this case is indicative of a pattern of prosecutorial excess that grew out of a climate of fear and prejudice following the attacks of September 11th,” said Donnaruma. “Such law enforcement techniques, and the convictions that resulted from them, are antithetical to bedrock principles of constitutional law and human rights. My clients thought it was critical that they weigh in on this important matter.”

Response from the Government

On April 13, the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of New York responded in a memo to the filing of the amicus brief. The memo does not discuss the substance of the 2255 application, except with regard to one meeting, and unfortunately the date of that meeting is wrong (specified as February 14, 2004 instead of February 12––see below under “Specific Issues Addressed by the Amicus Brief”). The memo also does not address what transpired at that meeting. The memo states that the government does not believe that another prosecutor should review the case, and that Aref does not have a right to discovery (release of evidence that may be favorable to the defense, legally required for the prosecution to give), though this determination will be up to the district judge in whose Court the 2255 application, the amicus brief, and the government’s memo have been filed. The memo reiterates the original government position that the issue of classified evidence was properly resolved at trial, and that no classified evidence was submitted at trial. It also concludes that all the issues raised in the 2255 application were already addressed in the appeals.

Preemptive Prosecution Program in the Aref-Hossain Case

The amicus brief claims that Aref was convicted under an unacknowledged U.S. government “preemptive prosecution” program, in which people who are perceived by the government to be suspicious in some way are targeted and convicted of some offense, simply to preclude the possibility that they might cooperate in terrorist activity in the future. The brief asserts that statements made by prosecutors after the trial indicated they had no evidence that Aref had engaged in any terrorism, but they were concerned that Aref might possibly help someone else facilitate a terrorist incident in the future. Thus they engineered the sting to “preempt” Aref from possibly becoming involved in a future crime. Unlike Hossain, the FBI decided not to show Aref a (fake) missile that was supposedly part of the plot, because the FBI was afraid that if Aref saw the missile, he might realize that something illegal was going on and be “spooked” (and withdraw), thus ruining the FBI’s frame-up. Prosecutors also acknowledged publicly that they never believed Hossain was a terrorist, and entrapped him only so they could use him to get to Aref.

Related Reasons to Reeopen the Case

|

Lata Duka, mother of three of the Fort Dix 5, at the March and Rally for Justice for Muslims, April 5, 2010 |

A July 2009 report by the Inspector General of the U.S. Justice Department about existing government surveillance programs found that no mechanism had been established in terrorism trials to identify or produce potentially exculpatory information, particularly classified information. A legal mechanism does already exist for allowing classified information that may be exculpatory into other trials. Called a Rule 16 or Brady motion, this procedure requires the government to make exculpatory evidence available to the defense. However, the amicus brief asserts that despite the legal requirement for producing potentially exculpatory classified information under a Rule 16 or Brady motion, this information was withheld by the prosecution in the Aref-Hossain case. The Inspector General’s report called on the Department of Justice to review prior terrorism convictions to determine if exculpatory information had been withheld in terrorism cases. So far, the Department of Justice has not begun such a review.

A strong measure of local support for reopening and reviewing the Aref-Hossain case was passage of an Albany Common Council resolution on April 5 that echoed the recommendation of the Inspector General: review all terrorism cases to determine whether defendants were given all legally required exculpatory information, including classified information, at their trials, so that their rights are assured under the Bill of Rights and the Constitution.

Specific Issues Addressed by the Amicus Brief

Aref’s 2255 application and the amicus brief assert that Aref was framed by the FBI for a crime of which he was unaware, and that Hossain was entrapped in a crime that he had no intention to commit. Aref was acquitted of all the charges in the sting prior to the last conversation with the government’s confidential informant, Malik, on June 10, 2004. (Aref was only convicted on charges after June 10, 2004.) In the June 10 conversation, Malik spoke in code to Aref about a missile plot, using the word “chaudry” instead of “missile.” The basic issue in the trial was whether the government ever told Aref the meaning of the code so he could understand the conversation and the plot. According to the amicus brief, without knowing the code, even the FBI conceded that Aref would not have understood the conversation.

FBI Agent Timothy Coll, who was in charge of the sting, testified at trial that Aref was told the meaning of the code by Malik at an earlier meeting on February 12, 2004, which was not recorded by Malik supposedly because his tape recorder fell off. Coll acknowledged, however, that he himself was not at the meeting and did not know what was said by whom. (Coll later contradicted himself by saying that Malik told him that Hossain had told Aref the meaning of the code.) According to the amicus brief, this was the entire testimony on record as to whether Aref was told the meaning of the code word; there was no direct testimony by anyone as to whether or not Aref was told the meaning of the code, or when.

According to the amicus brief, even though the government knew that it had no tape recording of the February 12 conversation, Malik never explained to Aref in any of the subsequently taped conversations the meaning of the code. Moreover, although Malik and another person who participated in the February 12 conversation were called as government witnesses at the trial, the government never asked either of them whether Aref had been told the meaning of the code. The amicus brief claims this shows that the FBI deliberately failed to tell Aref the code’s meaning; that it knew their own witnesses would not support the lie that Aref was told the meaning on February 12 or on any other date; and that it wanted to frame Aref by involving him in a coded conversation that he would not understand. According to the brief, there are good and valid reasons to believe that the February 12 conversation was in fact secretly recorded by the government’s warrantless surveillance program, and the brief claims this recording would show that the government never told Aref the meaning of the code. The brief claims that the government failed to produce the recording not only because it was classified, but also because it would show that Aref was framed by the FBI.

#