The Free the Fort Dix 5 Support Committee & Project SALAM

Rally In Support of The Fort Dix 5

August 31, 2010

Media Reports

Philadelphia Inquirer

George Anastasia from the Philadelphia Inquirer wrote a piece about the Fort Dix 5 rally held last Tuesday. Link to article

Posted on Sun, Sep. 5, 2010

Dix appeal spotlights two sides of security

By George Anastasia

Inquirer Staff Writer

They are collateral damage in the war on terrorism - victims, they say, of an overzealous Justice Department.

"What has America become?" Ferik Duka asked Tuesday as he stood with about two dozen relatives and friends at a protest rally in front of the federal courthouse at Sixth and Market Streets in Center City.

The government, he said, is "tearing apart innocent families."

Duka, whose three sons were convicted in the Fort Dix Five terrorism trial and are serving life sentences, insists that they and their codefendants are innocent.

Their lawyers filed a joint appeal last week seeking to have the convictions overturned. Their 149-page legal brief raised nearly a dozen issues, most of which the trial judge had rejected.

The arguments, now before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit in Philadelphia, are based on evidence, procedural issues, and rulings from the court proceeding.

In December 2008, after a 12-week trial, a jury found Dritan, now 31, Shain, 29, and Eljvir Duka, 27; Mohamad Shnewer, 25; and Serdar Tatar, 27, guilty of plotting to kill U.S. soldiers at the Burlington County Army base.

Defense attorneys and supporters of the Fort Dix Five concede that overturning the convictions is a long shot.

The arguments made on the Market Street sidewalk were intended to influence public opinion, however, not convince an appellate court. They stem from an issue at the heart of Ferik Duka's question.

Prosecutors and investigators in the case have declined to comment during the appeal process.

But proponents of investigative techniques employed in the case and others like it around the country cite two core principles to explain why terrorism investigations call for unique measures.

One was clearly enunciated after 9/11 by George Stamboulidis, a former federal prosecutor in New York who is now in private practice.

"The Constitution is not a suicide pact," said Stamboulidis, who accurately predicted in 2001 that the war on terrorism would include trade-offs.

There would be cases, he said, in which the right to privacy and protection from illegal search and seizure would be trumped by the need to thwart a plot aimed at death and destruction.

The other issue raised by investigators working terrorism cases is more harrowing.

"We cannot afford to be wrong," said one veteran law enforcement official.

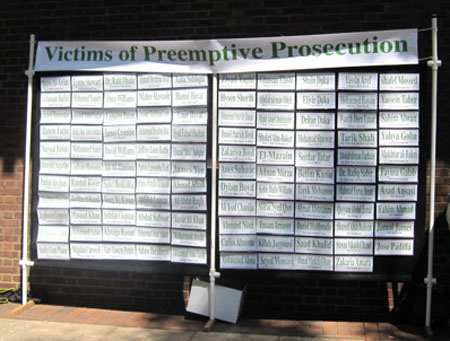

As a result, say supporters of defendants such as the Fort Dix Five, the government has adopted a policy of "preemptive prosecution" that undermines the judicial process.

Justice is not blind in these cases, they contend, but distorted. Individuals are arrested, they say, before any crime has been committed.

It's part of a "1 percent" policy first enunciated nine years ago when the government launched its war on terrorism, said Lynne Jackson, a coordinator in Albany, N.Y., for Project SALAM, a legal advocacy group that has taken up the cause of Muslims convicted in terrorism cases.

"If there's a 1 percent chance" that someone could be plotting a terrorist act, "then you have to take it as a certainty," Jackson said in explaining the approach.

Standing with supporters of the Fort Dix Five on Tuesday, the rights advocate said Muslims around the country had been "scapegoated" in investigations replete with distortions, misrepresentations, and entrapment.

"The plots are created by the government," Jackson said, pointing to evidence in the Fort Dix case - a trip to the Poconos - as an example. That trip, in January 2006, was the catalyst for the FBI investigation.

The defendants were targeted after a clerk at a Circuit City store in Mount Laurel was asked to copy a videotape of the Dukas and their friends. It included scenes from a Poconos shooting range where several men shot rifles and shouted in Arabic.

The defense argued during the trial that the tape, which also included horseback riding, skiing, and other activities, was merely a depiction of the men on vacation.

But authorities said the outing - and a second trip to the Poconos and a paintball excursion to a South Jersey farm - were part of loosely organized training exercises the defendants undertook as they planned "jihad."

Like much of the evidence at the trial, the facts of the Pocono trip are not in dispute. The same can be said about the hundreds of hours of conversations recorded by two paid FBI informants wearing body wires. The defendants said what they said.

The dispute is over what they meant and, as important, whether they intended to act.

Were the Fort Dix Five - men in their 20s who came to this country as children and grew up in middle-class Cherry Hill suburbia - plotting an attack on the military complex?

Was the plan - built around a scheme to gain access to the fort in a pizza delivery truck - real, or a fantasy hatched from the ramblings of a misguided and bombastic defendant (Shnewer), who was befriended by one of the informants and manipulated into saying and doing things later used to support a conspiracy charge?

Was this jihad, or was it sophomoric jingoism?

A jury decided that the plot had been real and that U.S. military lives had been at risk. The appellate court will be asked to examine legal arguments that, if valid, could be used to overturn the convictions or lead to sentence reductions.

But the issue on Market Street last week went beyond legal arguments.

Standing in front of the courthouse, Stephen Downs, a lawyer with Project SALAM, compared the situation to another controversial period in American history.

"It may take five years or 10 years, but I think we'll look back on this period the way people look back on the McCarthy era in the 1950s," he said.

Photos